Mormons aren’t a cult. I know because I’m a Mormon and I was in a cult. The cult had me far more brainwashed than Mormonism ever did or ever will.

I didn’t actually do the math.

I didn’t have the numbers for one side of the colon. But based on the proliferation of newsgroups, online critique groups, publishing forums in 2008, and the number of such denizens all trying to get published, I could guess. And it was huge.

Then there was me. 1 : x6214

Mormons aren’t a cult. I know because I’m a Mormon and I was in a cult. The cult had me far more brainwashed than Mormonism ever did or ever will.

I was 15 when I first found out how to go about querying and creating proposals. I even did that a couple of times for Reader’s Digest. I was rejected. It hurt, not because I was rejected, but because I was running out of time. A favorite author’s bio said she was 18 when she first published a book, which she wrote “on a whim”. If I hadn’t done it by 18, well … (Narrator: That was a lie. She was 25.)

I was eating Harlequin Presents romances for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I knew the formula. I knew the most popular tropes. I had plenty of ideas. I didn’t have such words in my vocabulary as “formula” and “trope.” It was a gut feeling, the natural rhythm of the way a good story is paced.

I never did get a Harlequin Presents romance written. By the time I could actually write a book, I liked Harlequin Superromances better and I trained myself to write within that word count (90,000 to 120,000). It felt more complete than the 55,000 words of Presents. Well, of course it would. It was double.

So here’s what happened:

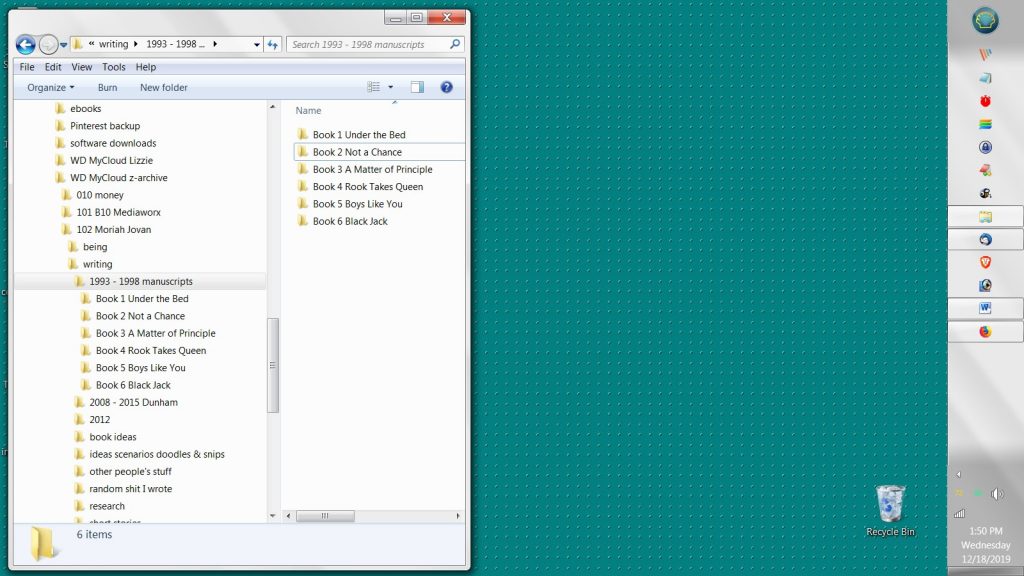

In 1989, I wrote my under-the-bed novel. The apprentice novel. The horrible one. The one you never want to see the light of day. It’s still out there floating around, I think.

In 1990, I wrote my next novel. It was marginally better.

In 1991, I wrote my third. It was good. I sent it to a publisher that had launched the careers of a bunch of NYT bestsellers. I got The Call. You know, the one where the editor calls you and congratulates you. Then … nothing. The publisher went out of business. Why? The parent company had bought it for a tax write-off and it made money. So bye bye Kismet. Yes, that was the publisher’s name. Kismet.

If you are a good writer, you WILL get published. Don’t give up.

In 1993, I wrote my fourth. It was really good. I sent it to Harlequin and got The Call. Sorta. The editor said, “I love this book. However, I bought one fairly similar last month that is not as good as yours, but I can’t break that contract and I can’t sell this to my editorial board. Send me something else. NAO.” I gave a brief rundown of book #3 and she passed.

So I got an agent with book 4. That relationship ended in disaster after she read book 2 and told me to get a therapist. (Narrator: That book was revamped a few times, published, and remains the fan favorite.)

In 1993, I started writing my pirate novel. I knew what I wanted to do. I also knew I didn’t have the chops to do it, so I fiddled with it for years.

If you are a good writer, you WILL get published. Don’t give up.

In 1993, I wrote book 5. It also got me The Call. An editor at Harlequin called me up on a Saturday morning and said, “I want to read the rest of this book. Overnight it.” She called me Tuesday evening and said, “I love this book—except the ending.” Me, having been trained to be a good, dutiful, well-behaved author, said, “I’ll rewrite it!” She sighed and said, “No, that would ruin the book. It has the ending it needs. I just can’t sell it.”

If you are a good writer, you WILL get published. Don’t give up.

In 1995, I was a senior in college in the creative writing program. My professor was the faculty supervisor of the uni’s lit rag. After my first assignment, he told me I had an A in the class and I could just skip the rest of the semester because he couldn’t teach me anything. But he would count it a personal favor if I stayed and did the assignments because he loved my work. That class was 8:00 a.m. after I’d spent the night working a graveyard shift at a gas station. You better believe I went to class.

I wrote a story. He was disappointed in me for giving it a “romance novel ending,” but otherwise he loved it. My senior advisor for my capstone project happened to be a Latin teacher (no idea why) who was absolutely fascinated by my creative process. She said, “I don’t care what you do, just tell me why and how you do it.” Okay, so I expanded on my story that had caught my attention.

It so happened that I was in Shakespeare 480 class or whatever really high number and we were studying Hamlet. I decided that somehow my religious allegory for the atonement (with a romance-novel ending) and Hamlet should go together like bread and butter. It didn’t. I couldn’t make that plot work.

If you are a good writer, you WILL get published. Don’t give up.

So I was bored at my graveyard job and in class and wrote book 6. That one got me a literary agent who loved it, but could not sell it, either.

If you are a good writer, you WILL get published. Don’t give up.

Let us stop a moment and draw the obvious conclusion.

It was about now I started messing with making my own galleys of book 6. I was never going to self-publish, oh NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO. Only bad writers self-published. It was the kiss of death. Even if you really were good, a publisher would never publish someone who had published himself. Still … that galley looked awfully pretty. I hesitantly called up a printer as if I were calling up a gigolo to take my virginity for me, knowing I was going to go to hell for it when I died, and said,

“Yeah, um … how … much … would this cost?”

“Twenty grand.”

“Bye.”

So even my attempt at committing the ultimate sin was unavailable to me.

I gave up. I had enough near-misses to let me know I wasn’t a bad writer, but clearly not good enough and I obviously didn’t know how to hit the Harlequin bullseye after all.

No, I didn’t give up trying to get published. I gave up writing altogether.

Fast forward to 2004. I’ve gotten married. I’ve had a baby. I’ve gotten a work-at-home profession as a medical transcriptionist and was doing okay. I’ve got no creative outlet. I refuse to write and only occasionally fiddled with my pirate novel, and once in a while, I tried to make that Hamlet-atonement plot that wouldn’t work, work.

My husband had read one of my books and liked it. He had urged me to query it again. I had. I had gotten swiftly and roundly rejected. Apparently, it hadn’t stood the test of time. In anger, I had burned all my manuscripts in the barbecue grill.

I’ve still got no creative outlet except … counted cross stitch. I love it. (Narrator: Loved. She killed that by making it into a business.) There were lots of things I wanted to stitch, so I learned how to convert them into patterns. I then went online and found out people who were “superstars” in the cross stitch pattern world had started out doing their own and just pitched them to shops and then got picked up by distributors. Self-publishing your patterns was the mark of a professional. So I did that. Turns out, what I like and what a lot of other people like aren’t the same, and the few who did like my patterns weren’t enough to pay the bills.

That fizzled after a few years of tinkering with it. I was okay with that. I’d had another baby. I was working my ass off at medical transcription because I had moved into a house that we should never have bought and had started having expensive problems. (Narrator: Two weeks after moving in, the back patio sliding door fell out. Just … fell out. That was a very cold winter.)

Fast forward to 2007.

One night, after having invoiced my contractor for my medical transcription work (it was a lot of money), I was very depressed. Not even my newly-doubled-dose of antidepressants was helping. (Narrator: Sometimes you don’t have depression. Sometimes your life just sucks.) As one gets older, one should be making more money for less effort. Otherwise, you’re not life-ing right. I sent my bill and sat there in the dark and looked at my computer. I opened up book 6 and I read my own work for the first time in years.

It was like somebody else had written it, and it was good. Like, really good. I went to bed even more depressed and discouraged and asking, “Why did I give up on myself?”

I woke up the next morning with the solution to my now-decade-old plot problem and I got to writing.

The rollercoaster car had left the station.