Someone sent me to an interesting article on a book I haven’t read, The Revolt of the Masses by José Ortega y Gasset. I hesitated to write this because I haven’t read the book, but I’m actually commenting on the post itself.

Someone sent me to an interesting article on a book I haven’t read, The Revolt of the Masses by José Ortega y Gasset. I hesitated to write this because I haven’t read the book, but I’m actually commenting on the post itself.

“The Smartest Book About Our Digital Age Was Published in 1929. How José Ortega y Gasset’s The Revolt of the Masses helps us understand everything from YouTube to Duck Dynasty.”

Are you, like me, puzzled to learn that Popular Science magazine recently shut down comments on its website, declaring that they were bad for science? Are you amazed, like me, that Duck Dynasty is the most-watched nonfiction cable show in TV history? Are you dismayed, like me, that crappy Hollywood films about comic book heroes and defunct TV shows have taken over every movie theater? Are you depressed, like me, that symphony orchestras are declaring bankruptcy, but Justin Bieber earned $58 million last year?

Why yes, I AM wondering what’s up with Duck Dynasty. I AM pissy about the constant retreads coming out of Hollywood. I AM annoyed that Justin Bieber can finance a country’s worth of symphony orchestras. (I’m not really sure about the Popular Science thing, though.)

All is well. I’m intrigued. I’m invested in this piece. I’m even slightly nodding at this:

Put simply, the masses hate experts.

It’s so true! They so do!

But there’s a little tickle in the back of my mind at the use of the word “experts.” Then come a few more phrases that make me squirm a little.

If forced to choose between the advice of the learned and the vague impressions of other people just like themselves, the masses invariably turn to the latter. […] The upper elite still try to pronounce judgments and lead, but fewer and fewer of those down below pay attention.

Huh.

- Experts.

- Learned people.

- Upper elite.

Ortega couldn’t have foreseen digital age culture, but he is describing it with precision. […] He would understand why Yelp reviews have more influence than the considered judgments of restaurant reviewers. He would know why Amazon customer comments have more clout than critics in The New Yorker. […] a friend who is affluent, educated, and a noted wine connoisseur. [who] now relies more on wine advice from websites where anyone can post their evaluations of different vintages.

And this is where the article loses me, but not because I’m in high dudgeon over the key words.

There are several practical/pragmatic variables here that the author of the piece hasn’t accounted for:

1. product accessibility

2. expert accessibility

3. artificial restrictions to #1 & #2

4. fallibility of experts

5. accessibility of product and information

6. unfulfillment of desires

1. The masses aren’t likely to have access to the restaurants a critic would. They may not have access to the symphony. They may not have access to wine.

2.

a. The masses aren’t going to be reading reviews of restaurants they can’t afford to go to. Further, before Google, one had to know where to look for this information, and one isn’t likely to look for that information for places they can’t afford.

b. There are only so many experts for so many things that we as a culture experience or want to experience. Not every book can be reviewed, much less in the New York Times, the holy grail of book review sections. There are not enough restaurant critics or column inches to review every eatery in any given town.

3. The point of an expert review isn’t to educate or recommend or dissuade or make such things desirable/accessible to the masses. It’s to put up a wall between the “experts,” “learned people,” “elite” and the masses. It’s a bright line: This is our turf. Do not cross. Who chooses which books and restaurants and wines get the column inches? The experts, the learneds, and the elites, who have absolutely no interest in talking to the masses at all. Those column inches are jealously guarded.

“Amateur” reviews on Yelp and Amazon are plentiful and varied. Every thing that the masses are interested in have an opinion behind them that they can use to evaluate their own choices. There are no column inch limits. There are no carefully curated lists, leaving off what the masses are actually interested in.

4. Experts. Now there’s an interesting concept. Expert. One who is more learned in X thing than all the other learneds in X thing. A synonym is “consultant.”

Except the masses have seen the experts. They have listened to the experts. They keep listening to the experts, because the experts are more learned than they are—and they know it.

And then … what they see is that the experts are wrong quite a bit of the time. They are confused. “This expert is saying X, and I want to believe him, but my lying eyes are telling me something else. Which one do I believe? DAMN MY LYING EYES!”

So they go on about their business because, in the grand scheme of things, people aren’t going to change if something’s working for them, even if an expert tells them they’re wrong, even if they want to believe that the expert is right. They’d rather just live with their vague feeling of being wrong because they can’t reconcile the viewpoint of the expert with their own experience.

5. The masses will go for what’s accessible, be it product or information, and they will turn away from carefully curated lists to find what they actually want. If they don’t find what they actually want, they’ll go for a substitute. Miley Cyrus is not Britney Spears is not Madonna is not Cher. But Madonna’s a decent substitute for Cher, and Britney’s a decent substitute for Madonna, and Miley Cyrus is—

My apologies to Britney, Madonna, and Cher.

Not only are these things accessible, they are in their faces. I do not see experts in their faces, giving them a reason to find a more erudite alternative.

6. The masses can’t make what they really want to have, what their ears and eyes want, so they have always had to take what they can get, whether they like it or not.

This is why genre self-publishing has taken over NY genre publishing. People found authors who will give them what they already know they want, but were not being provided. Authors don’t make tastes and trends. People who are looking for stories that resonate make those tastes and trends. Publishing takes pride in its gatekeeping, but it has a lousy record on what people actually want.

The article goes on with this:

The same people who denounce expert opinion about movies or music will praise a skilled plumber or car mechanic.

An expert opinion about movies or music is just that: an opinion. It has no basis in skill or objective measure. Further, movies and music are not staples of life; they are spices.

A skilled plumber will come out in freezing weather to replace a hot water heater. A skilled car mechanic will keep a piece-of-shit car running so someone who can’t afford a new car can get to work to feed their families.

How is this apples-and-Volkswagen comparison being made without irony and with a straight face?

The value of blue-collar expertise is accepted without question. The same people who get angry when I make judgments about the skill level of a pianist, would never question my decision to pay more to hire a superior piano tuner.

Shocking.

This is a peculiar state of affairs …

No it’s not. It’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what it is to be part of the masses.

At one point in The Revolt of the Masses, he complains about a woman who told him “I can’t stand a dance to which less than 800 people have been invited.” So how would the Spanish philosopher respond to the crowd mentality that seeks out viral videos with a hundred million views?

This is not difficult to comprehend. There are more people to choose from. This is not analogous to how many people vote for a YouTube video. This is analogous to having a billion YouTube videos to choose from.

Lastly, some more vocabulary:

… the possibility for barbarism to flourish in tandem with technology; or the unbalanced specialization which favors science over the humanities; or (in his words) “the loss of prestige of legislative assemblies.”

- Barbarism.

- Unbalanced.

- Not prestigious.

The masses are asses. My dad used to say that when observing what made popular culture. The case can be made, yes. Mobs have regularly shown themselves to be asses.

I’m not above making judgments on the taste of the masses, although I’ve learned that it’s wise not to do it publicly.

But to say that the masses are asses because they don’t listen to the experts is missing the point: they know who the experts say they are, but they don’t trust their advice and they know that the self-proclaimed experts aren’t there to sweep them into culture and a better appreciation of the humanities.

The experts are there to keep them out.

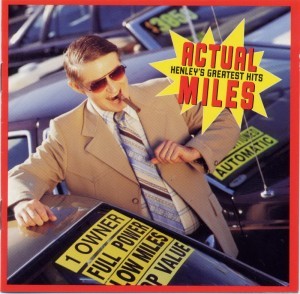

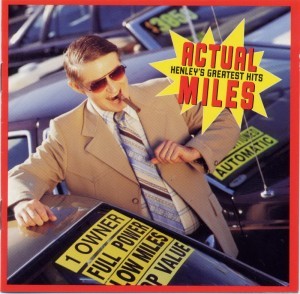

* “In the Garden of Allah” by Don Henley lyrics | audio

So when I was 16, I had a short-lived stint at Shoney’s as a salad bar attendant. I’ve never worked that hard in my life on a consistent basis. I didn’t do well for several reasons.

So when I was 16, I had a short-lived stint at Shoney’s as a salad bar attendant. I’ve never worked that hard in my life on a consistent basis. I didn’t do well for several reasons.