Justice had spent Saturday strolling around her lovely new neighborhood, marveling at the luscious lawns and tree-lined streets.

She had been walking on a concrete sidewalk in the shade of old trees. She could reach out and touch the feathery pink tufts of a mimosa tree. She could drag her fingertips across landscaping bricks. A soft breeze lifted her short curls and she could smell flowers and barbecuing and chlorine instead of cow shit. She could hear motorcycles and cars, screeching and splashing, lawn mowers and sprinklers.

She lived in a subdivision now. She felt something welling in her chest she couldn’t identify. It was almost too good to be true, but this wasn’t surreal like graduating from school to half-million-Monopoly-dollar job offers. It was normal, living here. Ordinary. Like the new clothes that fit well and flattered her and lifted her out of the realm of poor country girl. Their plainness, this ordinariness was a gift Knox didn’t know he’d given her.

When she came upon the clubhouse with the pool and the attendant asked for her address, then gave her a pass to the gate, she found herself choking up. “Thank you,” she whispered, looking down at it.

Rush lyrics play a large part in The Proviso, so much so that the female counterpart of the title-ish character calls it out:1 “Neil Peart wrote my hymns and Rush is my choir.”

Yet … as much as even the most poverty-stricken among us can get the message of “Subdivisions” thanks to ubiquitous teen TV dramas, kids who grow up in subdivisions aren’t.

Poor, I mean.

Poverty and people who think in Poor also have a large presence in The Proviso. Only one of the six leads grew up with money, and he doesn’t find money interesting or important, which is a manifestation of his privilege. The only other one who didn’t grow up poor grew up in … a subdivision. In San Diego. In the 80s. In the exact misery of the song.

Even though I referenced “Subdivisions” in The Proviso consistent with its intended message (Chapter 22 “Misfit So Alone,” Chapter 87 “Far Unlit Unknown”), I also subverted it because my heroine, the one to whom Rush speaks so deeply, lives in such abject poverty in a falling-down relic of 19th-century gothic revival in such a backwater of a town that the particular flavor of hell of growing up in a subdivision is, for her, a dream come true—or better yet, a dream she never thought to dream at all because her future is

Even though I referenced “Subdivisions” in The Proviso consistent with its intended message (Chapter 22 “Misfit So Alone,” Chapter 87 “Far Unlit Unknown”), I also subverted it because my heroine, the one to whom Rush speaks so deeply, lives in such abject poverty in a falling-down relic of 19th-century gothic revival in such a backwater of a town that the particular flavor of hell of growing up in a subdivision is, for her, a dream come true—or better yet, a dream she never thought to dream at all because her future is

pre-decided

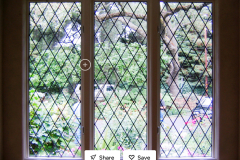

Now, the subdivision she is suddenly dropped in the middle of isn’t a rich one, either. It’s old, mid-1960s, in a sprawling ranch that tries to look French provincial, a house that still has Mamie pink tile and Formica in its kitchen and bathrooms, and sits at the very back of the developed land, waiting for the day it gets razed and replaced with closely set mcmansions. There are newer houses farther away from her upgraded home, and so there’s a clubhouse with a pool.

The house and neighborhood are not glamorous. They’re not even of the caliber of the Toronto subdivisions referenced in the song. She’s savvy enough to know that the house is wildly out of date, even if someone did attempt to modernize it with avocado green shag carpet and a harvest gold refrigerator, and the fact that the trust-fund guy she’s married to is fine with Walmart flat-pack furniture isn’t normal, nor should it be—but to her, the whole setup is magical.

But not overwhelming.

After all, you can take a poor country girl off the farm and plop her in a society matron’s living room, but there’s gonna be an immediate need for a therapist. The mint-ish 1960s ranch is as big a step up the socioeconomic culture scale as any mature person could handle. The mcmansion comes next.

This isn’t just about peer pressure. It’s a law of social survival. The song argues that in these kind of controlled environments, individuality isn’t just discouraged, it’s actually a liability. And that message, it became an anthem for a generation of outsiders. It speaks directly to the deep-seated adolescent fear of being different, of being rejected for not living up to the unspoken standard. —Neil Peart

So the next time “Subdivisions” comes on the radio, we can nod and give the generic middle-class North American teen his angsty due, but then remember that one person’s prison is another person’s paradise.

______________________________

1. The book’s not metafiction by any stretch, and it never breaks the fourth wall, but it is somewhat self-aware.